CMYK Explained

The obscure and almost unknown letters and meaning of CMYK it is as much as mystery as WYSIWYG lettering. But why should you care? It may not apply to you in the first place… unless you are a photographer who wishes to make a living snapping pictures and getting them published in print magazines and other printed media! If this applies to you, keep reading!

The reason for this blogpost is to bring an awareness to photographers who are not familiar with color separation and what happens to your images after they leave your camera and end up in desk of editors on their way to be printed. As juicy and popping as the colors might have been when you shot the images or adjusted them in your editing program, there’s a strong chance and almost a definite possibility they may not always work out as vibrant as you see them on your computer screen when they’re printed.

The reason for this blogpost is to bring an awareness to photographers who are not familiar with color separation and what happens to your images after they leave your camera and end up in desk of editors on their way to be printed. As juicy and popping as the colors might have been when you shot the images or adjusted them in your editing program, there’s a strong chance and almost a definite possibility they may not always work out as vibrant as you see them on your computer screen when they’re printed.

CMYK (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black) in layman’s terms is a language that printers, even the most basic one like the one on your desk at home, read and understand. Most of the printing presses in the world require your images transferred to CMYK format before they can be printed (and there goes the popping colors).

What happens is when you convert your images to CMYK, it flattens the colors to certain values and percentages that a printing press can comprehend. This can be very disappointing experience. CMYK colors look dull compared to RGB images and render a totally flat color saturation when compared. (Now, if you are shooting for the Internet or Internet-based publications, then you have nothing to worry about. Your images can remain in RGB and as vivid as your eye can take.)

Here’s an interesting story I would like to use as an example of the many hidden wisdoms that are usually gained via experience. One of our STC attendees shoots a cover for Playboy without further thinking about the color process, resulting in possible challenges from the publication, or even a missed publishing opportunity. Thankfully, the STC wisdom and his studies has taught him well and he has shot several versions and color combinations for the editors to choose from, which we all expect to see the resulted that will be published soon.

CMYK or RGB Color?

Digital cameras and scanners create images using combinations of just three colors: Red, Green and Blue (RGB). These are the primary colors of visible light and this how computers and televisions display images on their screens. RGB colors often appear brighter and more vivid specifically because the light is being projected directly into the eyes of the viewer.

This is an “additive” process in which the three colors are combined in different amounts to produce various colors. It is called “additive” because you must add varying amounts of two or more colors to achieve hues and values other than the three basic red, green and blue colors.

Computer monitors and televisions vary the amount of each color from 0 to a maximum of 255. Equal maximum amounts of all three colors (often expressed as R255, G255, B255) creates white. The absence of all three colors (R0, G0, B0) creates black. Equal amounts of all three colors somewhere between 0 and 255 will create varying shades of gray.

RGB (additive) Color

Many photo and graphics applications default to the RGB color space because computers use RGB to display color themselves. It is easier. Most software and even desktop inkjet and laser printers assume that you are using RGB color to simplify things for users. However, strange as it may seem, all desktop inkjet printers actually use CMYK (or at least CMY) to produce color documents. Not all printers use the black cartridge when printing color, the cheapest models may use equal amounts of Cyan, Magenta, and Yellow to produce Black (often poorly).

What is CMYK or Process Color?

Based upon Sir Isaac Newton’s Color Circle, Four-color process printing was originally developed in the late nineteenth century along with the halftone process for reproduction of continuous tone images (photographs) and has been used for over 100 years to reproduce color images. The colors Cyan, Magenta, and Yellow appear directly opposite the Red, Green, and Blue on the Color Circle devised by Newton over 300 years ago.

.jpg)

Newton’s Color Circle

Professional printing presses print full color pictures by using the colors Cyan, Magenta, Yellow and Black (CMYK). In this “subtractive” process the various inks absorb the light reflected from the underlying white paper to produce the colors that your eye sees. The colors that you see are those colors, which were not absorbed by the ink. It is called subtractive because when you subtract the other colors, the color that is left is the color that you see.

In the CMYK color system equal proportions of Yellow ink plus Cyan ink produces Green, Yellow ink plus Magenta ink produces Red, and Cyan ink plus Magenta ink produces Blue (actually more like purple to most eyes). Various color shades and values are achieved by varying the relative amounts of the four colors. Black ink is added to improve the quality of 3-color blacks, to provide added detail to images, to speed drying, and to reduce overall ink costs, thus the name: Four Color Process.

CMYK (Subtractive) Color

This is the Four Color Process (also known as Process Color or Full-Color) printing that comprises the vast majority of magazines and marketing materials you see every day. Process color is generally very good for reproducing pictures but there are some types of color that it cannot reproduce well. This is because the gamut (or range) of reproducible color for Process Color is not as wide as that of RGB color. As a result, certain intense values of colors such as Orange, Green, Blue, and other bright colors can sometimes appear dull or even dirty. On the other hand, bright Reds generally reproduce very well.

That is not to say that CMYK color looks dull or dirty. Just look at any color magazine such as The National Geographic or fine coffee table book and you will see that it does a very god job of reproducing nearly every color that might be needed. For those special colors that cannot be satisfactorily reproduced by CMYK there is always spot color (special extra inks that are mixed to match a specific color or even a customized color). Spot colors are often used for metallic and other special effects colors.

It is best to select any colors you use for fonts, images or other design elements in your layout using CMYK definitions instead of RGB. That way, you will have a better idea of how they will appear in your printed piece.

RGB Must be Converted to CMYK Color in Order to Print

At some stage your RGB file must be translated to CMYK in order to print it on a printing press. It is best if you do the RGB to CMYK Conversion of your images. You will have more control over the appearance of your printed piece if you convert all of the images from RGB to CMYK before sending them to print. Be aware that it is possible to create colors in RGB that you cannot reproduce with CMYK. These are beyond the CMYK color range or “out of the CMYK color gamut”.

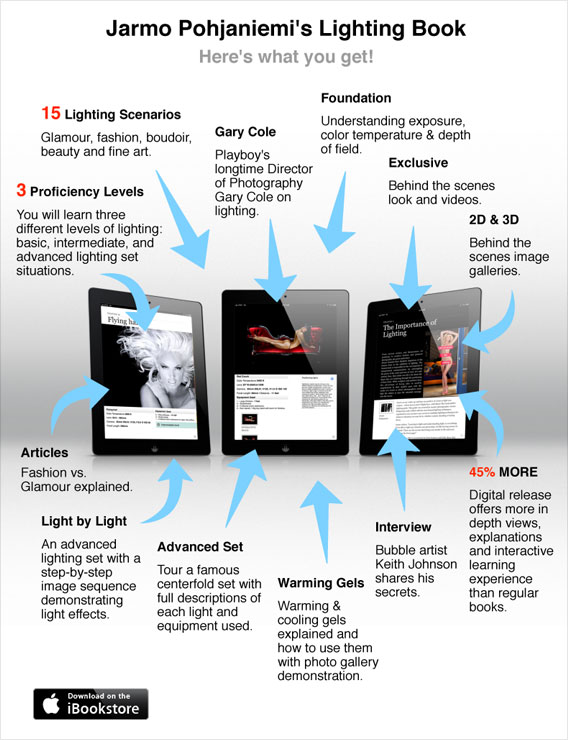

Here are some examples of how various RGB colors convert to CMYK:

RGB Colors (what you see on screen)

CMYK Colors (printing inks will do this)

You most likely won’t notice this kind of color shift in a color photograph. It is more likely to happen if you pick a very rich, vibrant color for a background or some other element of your layout. It probably won’t look bad, it just won’t look exactly the same. But it may not be noticeable at all either.

www.ShootTheCenterfold.com

© 2014 Copyright ShootTheCenterfold.com. All rights reserved.

Hello Jarmo. great article on photo color print work . Very clear and concise. You did mention us photographers would get best results of we convert from RGB to CMYK ourselves. How about another article from you on how to do this ?? Jack Henry