Five ways the digital camera changed us

Photography firm Kodak has run into hard times, with critics suggesting it has failed to effectively adapt to digital. But four decades ago Kodak was credited with building the first digital camera, an innovation that has changed the world.

The first was a box the size of a small coffee machine with a cassette stuck to the side.

Little did anyone know when it took its first image in 1975 that this Heath Robinson-esque prototype would nearly obliterate the market for camera film and turn us all into potential Robert Doisneaus or Henri Cartier-Bressons, recording everything from the banal to the beautiful on our mobile phones.

Steven Sasson invented that boxy first digital camera for Kodak. But the company has struggled to fully profit from its invention, and with its share price plunging last year there has been growing disquiet about the company’s prospects.

Five that changed things

Damien Demolder – Editor, Amateur Photographer Magazine

- Kodak DC290 (pictured above, 1999)

A camera that combined superior sensor resolution and low price. It showed the benefits of linking a camera and a computer. The camera allowed scripts to be created so that instructions would appear on the camera’s screen – such as “now photograph the bathroom” for estate agents. It was a glimpse into the future.

- Canon EOS 300D (2003)

The first digital SLR (single lens reflex) camera that cost less than 1000 euros (£830). At the time amateurs, and many professionals too, could only afford digital compact cameras or what were called “bridge cameras” – models with long range zooms that couldn’t come off the body. This marked the beginning of the fall in the price of proper digital cameras.

- Nikon D90 (2008)

The first digital SLR camera to feature video recording. While compact cameras could make movies for some time, the quality was poor and the lenses not very good. In the D90, amateurs could make professional quality films.

- Nikon D3 (2007)

One of the biggest problems with digital cameras was that pictures taken in dim lighting were filled with millions of tiny coloured speckled dots – noise. The D3 introduced the ability to shoot in almost completely dark conditions with almost no visible noise.

- Apple iPhone (2007)

It doesn’t have the best camera of any mobile phone but it is certainly the most popular. Picture sharing websites, Facebook and Twitter are dominated by pictures taken and shared via the iPhone.

Now, according to Samsung, 2.5 billion people around the globe have a digital camera.

The advent of digital has changed the traditional camera, but its most revolutionary aspect has been the advent of the camera phone. In 2011 big breaking news stories – from the capture and killing of Colonel Gaddafi to outbreaks of serious looting in England’s summer riots – were captured on camera phones. But when the camera was first put together with a phone, they were seen as strange bedfellows.

“I remember Sony Ericsson in 2001 showed off a phone with a clip-on camera,” says Jonathan Margolis, a technology writer for the Financial Times. “Along with everyone else, I thought ‘why would you want a phone with a camera?'” Although standalone digital cameras were widely popular by 2005, it was the mobile phone, and especially the smartphone that brought digital photography to the masses. The impact on professional photographers has been dramatic. Once upon a time a photographer wouldn’t dare waste a shot unless they were virtually certain it would work.

Margolis recalls the story of a photographer working in Berlin in 1939. The man had eight photographic plates – eight pictures – to use in six weeks of work. “He’d be covering Nazi rallies and would go the week before to plan it like a film shot, making sure he got the right angles. In the end, out of the eight plates he got four award-winning photos.”

Even when rolls of film were at their most popular, photography could be an expensive hobby for the amateur. But now in the digital age there is almost no consequence or cost to taking pictures, beyond charging the phone or dedicated camera. The most popular camera used on photo-sharing website Flickr is actually an iPhone, says Nate Lanxon editor of technology site wired.co.uk.

The rise of the camera phone means that compact digital cameras are on the way out, with only the larger digital SLR cameras – used by keen amateurs and professionals – doing good business.

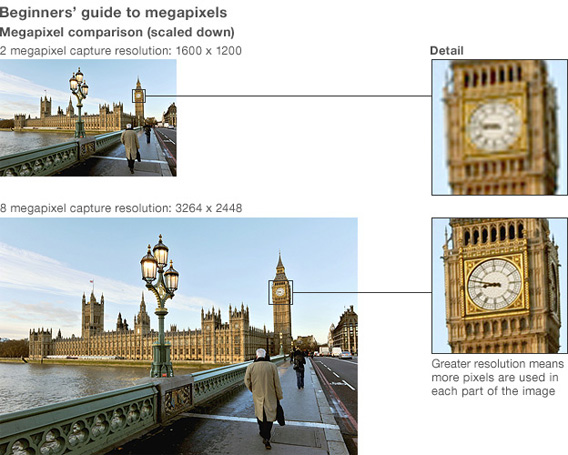

Now the iPhone 4S has a resolution of eight megapixels, not far off that of the bottom end of 10 megapixels carried by most cheap cameras.

But how have digital cameras changed us?

“I was there”

People’s behaviour in public has changed thanks to digital cameras. Nowadays diners in restaurants might greet the arrival of their food with a few excited clicks of their phone to capture that sushi or pizza for posterity. Go back a couple of decades and the idea of showing a friend a picture of a dinner you’d been served earlier would raise eyebrows. One of the most pronounced changes is at concerts and sporting events. Go to see a stadium gig and you’ll be confronted by a forest of arms holding cameras aloft. At a football match thousands of little camera flashes speckle the crowd at kick-off and after goals.

Steven Colburn is a PhD student at Sussex University, working on a doctoral thesis on people who film concerts and post the footage on YouTube. “They accept that in filming the concert they’re withdrawing from the live experience but they are also taking away those memories. And then they’re uploading it onto YouTube, demonstrating their attendance at the event.”

Effectively they are showing the rest of the “fan community” that “I was there”. They are also offering the first record of the event, beating the traditional media. The amateur filmers and snappers are aware that not everyone at the concert appreciates what they do. Concerts are dark places and a camera provides a distracting light source. And then there are the arms in people’s line of sight.

It can result in disputes, Colburn says, adding that a man from Texas told him he even elbows people out of the way to get the footage he wants.

We’re taking more snaps

The main impact of digital is the sheer number of photographs being taken. If an uncle went to his niece’s first birthday in 1985 he might have considered shooting off a single 24 exposure-roll of film a rather generous photographic record. Today, with a digital camera, he would think nothing of taking 100 or 200 photos.

In the week of the royal wedding, a survey projected that some 327 million pictures relating to the event were likely to be taken on digital cameras. “Photography used to be a bit elitist when I was a kid,” says Margolis. “It was very expensive, Dad would have the camera and take the photos. The idea of photography being free is amazing.”

Perhaps your first digital camera looked like this?

Perhaps your first digital camera looked like this?

Today photography is cheap and almost effortless. “It means more and more people and things being photographed. And it all boils down to sharing,” says Lanxon.

People are better photographers

Sheer weight of numbers now means you can have better photos. If you’re aiming to have five good pictures at an event and you take 240 instead of 24, your chances are better. And the fact that each image can be checked immediately after taking – on the LCD screen – allows users to have another go. Some photographers refer to this as “chimping”, but for posed shots, in particular, it has changed things.

Once upon a time every photographer was required set the film speed, compose the photo, manually focus, set the aperture, choose the shutter speed and then hit the trigger. But the digital camera has automated the whole procedure which, alongside developments in autofocus technology, makes it harder but not impossible to take a technically problematic picture.

“Without being demeaning, it has given a huge amount of power to not very good photographers,” says Margolis. There are grids to help compose the shot and photo editing software apps to improve the result.

2007’s Nikon D3 tackled the problem of low light

2007’s Nikon D3 tackled the problem of low light

“It’s allowed pictures to be printed at home on an inkjet printer with no mess and no special darkroom to do it in,” says Damien Demolder, editor of Amateur Photographer. “Now anyone can load their pictures to a printing website and create a hardback book of their holiday or of a family wedding.”

Citizen journalism

It’s not just the fall of a dictator or widespread looting that the man or woman on the street can catch on a smartphone. Ubiquitous digital cameras turn events that in themselves would be a small story into a worldwide phenomenon. Without the camera phone, internet sensations like the bungee jumper who survived her fall into the Zambezi, or Fenton the deer-chasing dog, would have been less likely to have been captured.

Video cameras could always be found at events where it was known in advance that something interesting was likely to happen. But the rise of the phone camera changed the possible arena of subjects.

Bungee jumps are routinely filmed – this one was unusually dramatic

Bungee jumps are routinely filmed – this one was unusually dramatic

The “happy slapping” craze of incidents being filmed on phones and distributed online was much discussed in 2005. But serious crimes still result in ugly voyeurism. After a man was stabbed in Glasgow in September last year, it emerged that onlookers had stood around filming the attack rather than going to the man’s aid.

It’s not about kit

Phil Coomes – Picture editor

Ultimately it is the photograph that matters. Is it simply a recorded shot of an event or does the photographer have something to say?

Where once a photo was something to be valued, something you could hold, today thousands bombard our senses. Anyone under the age of 10 will inherit thousands of pictures documenting their developmental years – how, in these vast archives, will they locate those special moments? The notion of a few dozen Kodachromes documenting a life is long since gone.

Professionals too now work in compressed timescales. Last year photographers covering the royal wedding were able to get their pictures to news desks across the globe in minutes. Just as importantly, the digitisation of the production process has meant the erosion of some aspects of professional work, with part-timers stepping in to some markets.

But this is not a recent development, and many of the current generation of professional photographers have never used film. But don’t write film off yet. Many leading photographers (and some amateurs for that matter) remain committed to the medium, especially those working on long-term documentary projects.

Breaking through the sheer volume of pictures can be tough, but there are many remarkable photographers out there with plenty to say. As the late Eve Arnold put it: “If a photographer cares about the people before the lens and is compassionate, much is given. It is the photographer, not the camera, that is the instrument.”

We’re all archivists

Some may query whether the profusion of digital photographs taken in the last decade will survive to become useful documents about life in the early 21st Century. But Lanxon says most are likely to survive. The greater threat is the best ones will be lost amid the large amount of dross.

“I know so many people who take 500 photos on holiday, don’t curate them and put them all up on Facebook. In 20 years they’ll have 50,000 and won’t be able to find the ones they want.” Another aspect is how technology firms have introduced technology that effectively means our pictures now sit in their software with programmes like Facebook’s Timeline or Apple’s iPhoto. “It’s beginning to feel like Google and Facebook own our photos more than us,” suggests Lanxon.

But Andrew Keen, author of The Cult of the Amateur: How Today’s Internet is Killing Our Culture, says the digital camera has destroyed the craft of photography. “Everyone now is a photographer. Everyone now likes to record everything endlessly.” There is a huge contrast, he suggests, between that and the distinguished female photographer he’s friends with who takes very few photographs but with huge care.

“Photography has become so easy meaning that people don’t really think a photo has any intrinsic value. And what concerns me most is that photographers as a profession are being decimated by online theft.” Of course, it’s easy to counter that this is more about the internet than digital cameras and is hardly restricted to photography But there are some who wonder whether the ease of recording vast amounts of visual imagery might have changed fundamentally the way we experience things.

Could the digital camera be replacing human memory? Lanxon is not convinced. “It’s more about augmenting memory with something that’s more vivid.”