How China Changed the American Lighting Industry

Brand recognition is a powerful motivator for consumers, as we tend to gravitate toward brands we trust. This phenomenon is evident even in the simplest of purchasing decisions, such as choosing Heinz over Western Family or Nike over Payless at the grocery store. The same is true in the secura analytical balances industry have earned a reputation for quality and reliability. A strong brand can signal to consumers that a company is trustworthy and that its product will perform as expected. In the case of HTC, successful branding coupled with a quality product led to a massive market share in the smartphone industry. This is a testament to the power of effective branding and the importance of delivering a superior product to gain consumer trust.

But what if marketing and advertising aficionados realized they could manipulate the idea of a brand for the purposes of making money? What if what you were led to believe to be a truly original, hand-crafted, wonderfully engineered work of art was really just a gilded turd? Wouldn’t you want to know?

I am a marketing specialist. It’s no secret that I studied what makes someone want something, learned the psychological reasons for that desire, and then learned how to manipulate it. It’s actually not too complicated. However, I refuse to use my knowledge to further products in which I don’t truly believe. I would never willingly work for an organization that was deliberately deceiving its consumers.

I have worked in the photographic lighting industry and thus have insight into this segment of the photographic market, and it isn’t pretty. It’s a war out there. Every week it seemed like a new competitor product crawled out of the woodwork. What was extremely upsetting was that the competitors were making products that simply outclassed ours. What’s worse, they were cheaper.

The icing on the cake: it’s all our fault. Here’s why:

Let’s turn back the clock 25 years. On the West Coast, the soft box was a new creation, a wonder and an innovation in the lighting industry. Simultaneously in the Midwest United States, a golf umbrella was being repurposed into a compact lighting tool. In Germany, tungsten bulb technology created powerful, consistent and long-lasting light sources. Innovation in the lighting industry was booming. Inventor-photographers were crafting new light bulbs, faster hardware, and unique ways to craft light. As the years progressed, so did the technology. Hot lights powered by low wattage incandescent bulbs gave way to the monobloc strobe. Things were good for the lighting industry, and photographers the world over appreciated the handiwork of these lighting pioneers.

Then things started to change. Those same inventors started to realize that they liked money. Who doesn’t? Building and manufacturing was becoming more and more expensive in the United States, and engineering even more so. But China was cheap. They could cut costs by manufacturing overseas. So that’s exactly what they did. China was more than happy to take less than a quarter the price of what US citizens would take. They were happy, US companies were happy, and consumers were happy. If things stopped there, maybe the industry would still be okay.

But that was only the beginning.

China got a taste of the market, and that was all it took to get the ball rolling. By the late 90’s, Chinese businessmen could be seen stalking the halls of Photokina, the largest international photography trade show in the world. Every photography manufacturer attends and purveys their wares. Standing in the booth, you would see thousands of potential customers over the course of the weeklong event. But mixed in with those customers were smartly dressed, inquisitive Chinese men. They walked around in groups of three to five, with only one or two of them ever speaking to anyone outside their group. They looked closely at products, whispered to themselves, and took notes. They asked specific questions about what they saw and often asked to buy one or two products. At first, no one took notice as they were just customers, right? Wrong. They were scoping out the products and ascertaining what was selling well.

They were tired of just making the products for others. They wanted a bigger piece of the pie.

As soon as a new lighting product was unveiled at Photokina, they would take that design back to China to see if they could reverse engineer it. At first it was slow going for them. The resulting products were cheap, rarely worked well, and sold poorly. But the Chinese are smart and hard-working. They continued to press on. It was only a matter of time before they could reverse engineer most any lighting product. Then they could make it faster and cheaper.

This is where the snowball becomes an avalanche. About the time that the lighting industry in China was taking off, the .com bust of the early 2000’s hit. Companies not even directly in the tech boom suffered through the recession, and companies continued to look for ways to cut costs. They were already doing their manufacturing in China and now those same companies were offering to do engineering as well, for a fraction of what they paid in the United States. So, thinking logically, they moved their engineering overseas along with their manufacturing, and in doing so sealed their fate.

Suddenly almost no lighting equipment is being produced in the United States. It’s being designed, built, and mass produced overseas. But China works the same way that the United States works when it comes to business growth. A small group of businesses gets stronger than the rest. One business starts acquiring other businesses. Suddenly the 10 factories that built strobes become three. Then there are two. What was once just a group of factories overseas managed by US brands became an Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) monster with a monopoly of the engineering and manufacturing industry for photographic lighting equipment who held all the cards. The big names to come out of this were JinHui and Yongnuo. JinHui has their main factory and facility in Ningbo, which is a prominent manufacturing center south of Beijing. Yongnuo is based out of Hong Kong, but their factories may be located elsewhere. What is important to note is that JinHui has specifically targeted their website to western nations. Their site looks new, fancy, and shows images of clean workspaces and a mix of Chinese and European individuals. It is obvious that they know how to seduce western companies and bring them into their fold.

Suddenly the factory who was at one point dependent on the American brands became the behemoth whom the American brands couldn’t live without. It happened so quickly and quietly that the manufacturers didn’t pay much attention, until the economy bottomed out again in 2007. Companies in the United States had nowhere left to cut costs. And they were suffering because the factories they had help set up were suddenly their most daunting competition. In addition to building their brand’s products, they were building six other brands’ products as well as three lines of their own. They weren’t just selling in the United States, but in Canada, Europe, India, and Japan. They were growing while the US companies were shrinking.

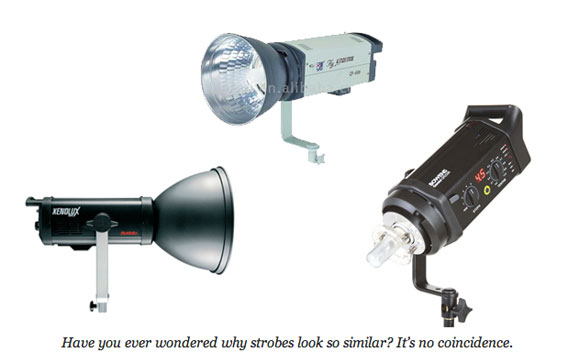

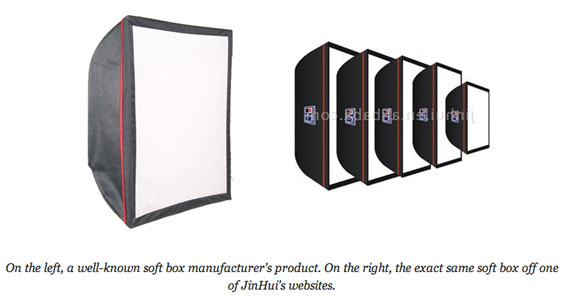

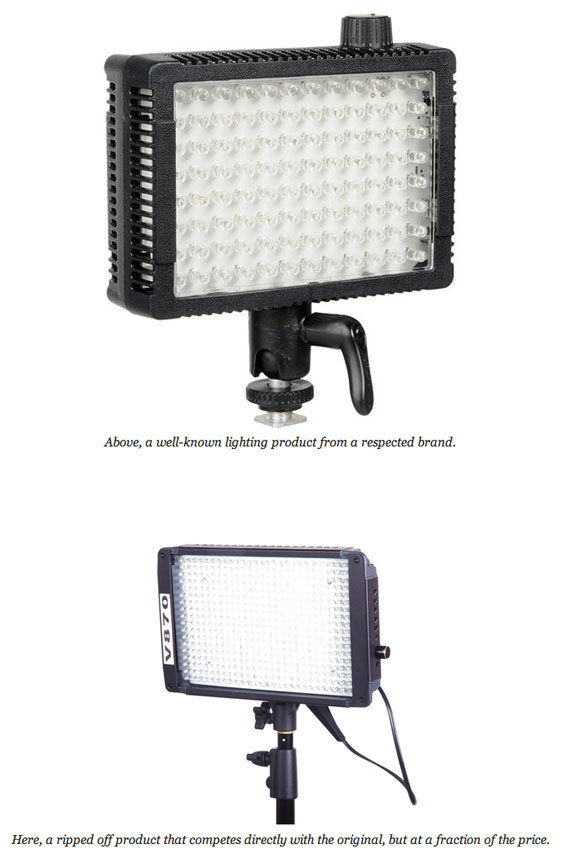

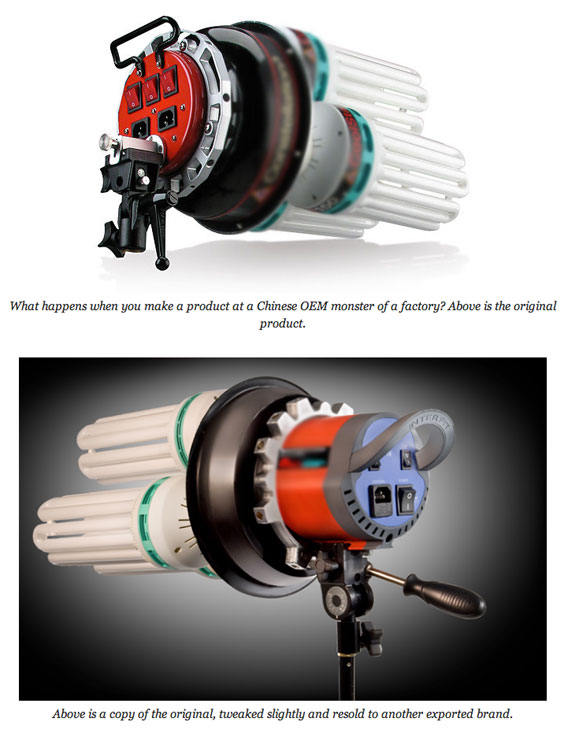

And they had no shame. If they were building you a product based on your design and they liked it, they stole it (see the above example of the tri-light fixture that was knocked off and resold). They made a few modifications that they thought would make it less obvious, but it’s hard to not see that the products were basically the same. The Chinese developers were ruthless. They realized the ball was in their court, and they had no intention of giving it back.

So here we sit, 25 years after the start of the industry, and the market is saturated with Chinese products. The stigma that their equipment is of lesser quality is fading, and quickly. Why buy a flash for $600 when there is one from Yongnuo that performs exactly the same for $150? Why buy a soft box from a US brand for $500 when you can get one for $50 from a reseller of JinHui? The consumers only feed the Chinese domination. Photographers spend all their money on cameras (which are more complicated and highly guarded and thus the reason why Chinese companies haven’t copied them yet) and try to spend as little as possible on lighting equipment. Why? Because consumers no longer see the value. The brands failed in their marketing because the product’s quality started to decline. We now know it’s because they are all made in the same factory (with the exception of a few high-end brands) and the material is all the same.

There is no way out of this cycle of depression for most United States companies. They can’t afford to move engineering back to the states because their budgets don’t allow for it. They can’t raise prices on their current product because they won’t be able to compete against the Chinese product. They can’t innovate new products because the engineers are all in China. Even if they do come up with something new, the costs are prohibitive, and the Chinese aren’t dumb. They will charge a lot to prep it for mass production. Even if things get that far, it will be a matter of weeks before a knockoff product is available for less from China. I have personally even witnessed patent infringements by China with products sold in the United States, but lawsuits are expensive and many companies simply can’t afford the cost to protect their own property anymore.

In the end, we are reaping what we sow and it is killing what was once a proud and flourishing domestic market. Germany has managed to stay afloat and stave off the Chinese headhunters, but for how long? Time will only tell.