Hugh Hefner, Playboy Founder and Leader of ’60s Sexual Revolution, Dies at 91

Both lauded and criticized by feminists of the era; the media icon convinced Hollywood starlets to reveal more of themselves on his pages than perhaps anywhere else. The interviews were great, too.

Hugh Hefner, who parlayed $8,000 in borrowed money in 1953 to create Playboy, the hot-button media empire renowned for a magazine enriched with naked women and intelligent interviews just as revealing, died of natural causes Wednesday at the Playboy Mansion in Los Angeles. He was 91.

“My father lived an exceptional and impactful life as a media and cultural pioneer and a leading voice behind some of the most significant social and cultural movements of our time in advocating free speech, civil rights, and sexual freedom,” read a statement from Hefner’s son, Cooper Hefner, chief creative officer of Playboy Enterprises.

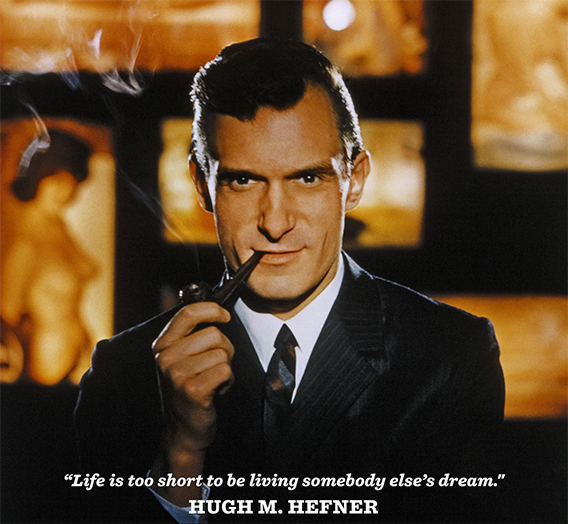

While most famous for Playboy, the businessman dabbled in all forms of media, including hosting his TV shows, beginning with Playboy’s Penthouse in the late 1950s and early ’60s. Shot in his hometown of Chicago and syndicated, the show featured Hefner in a tuxedo and smoking a pipe surrounded by “playmates” and interviewing such celebrities as Bob Newhart, Don Adams and Sammy Davis Jr.

The show boosted his personal and professional reputation and promoted what eventually became known as the “Playboy Philosophy,” a lifestyle that included politically liberal sensibilities, nonconformity and, of course, sophisticated parties with expensive accouterments and the ever-present possibility of recreational sex — though Hefner maintained he was a relatively late bloomer in that department, remaining a virgin until he was 21.

Hefner followed that show with Playboy After Dark, which had a similar format but with more rock ‘n’ roll, including appearances by The Grateful Dead, Three Dog Night, Harry Nilsson and Linda Ronstadt. The syndicated Screen Gems show was taped at CBS in Los Angeles and ran for 52 episodes in 1969-70.

Hefner also co-produced hundreds of Playboy-branded videos and a few feature films, such as Roman Polanski’s Macbeth and Monty Python’s first film, And Now for Something Completely Different, both released in 1971. He had been a sought-after guest on TV shows as far back as 1969 when he played a Control agent on an episode of Get Smart, and more recently he appeared on Curb Your Enthusiasm, Entourage and Sex and the City, as well as in animated shows like The Simpsons and Family Guy.

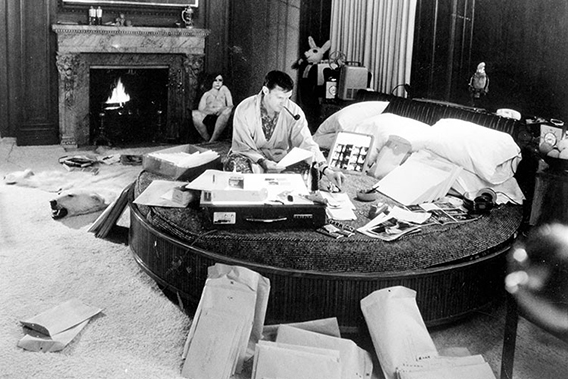

Hefner also made cameos in several movies, most recently 2008’s The House Bunny, which told the fictional story of a Playboy “bunny,” played by Anna Faris, who has been kicked out of the Playboy Mansion, the famous real-life, 22,000-square-foot house in Los Angeles where Hefner lived for more than four decades and where he hosted famously decadent parties that attracted celebrities A-list through D.

Hefner was a staunch supporter of abortion — including helping to finance the landmark Rowe v. Wade decision in 1973 — and more recently was an outspoken advocate of same-sex marriage, and his dedication to such issues (along with his distribution of pornography) made him a pariah in some religious circles. “By associating sex with sin, we have produced a society so guilt-ridden that it is almost impossible to view the subject objectively,” he wrote in 1963 in one of his many broadsides aimed at Christian leaders.

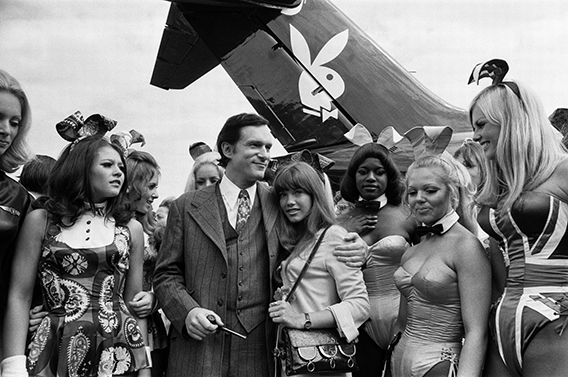

Hefner also launched the Playboy Channel in 1982, a premium cable outlet that has since been sold and rebranded Playboy TV and is more explicitly sexual than when it was under his purview. He created The Playboy Club nightclub chain that still exists as a novelty, but in its heyday in the 1960s, the era’s biggest stars – including Rat Packers Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin — could be spotted holding court while the barely dressed bunnies served food and drink. All this was loosely reflected on the NBC series The Playboy Club, which was set in 1961 and canceled in 2011 after just three episodes aired.

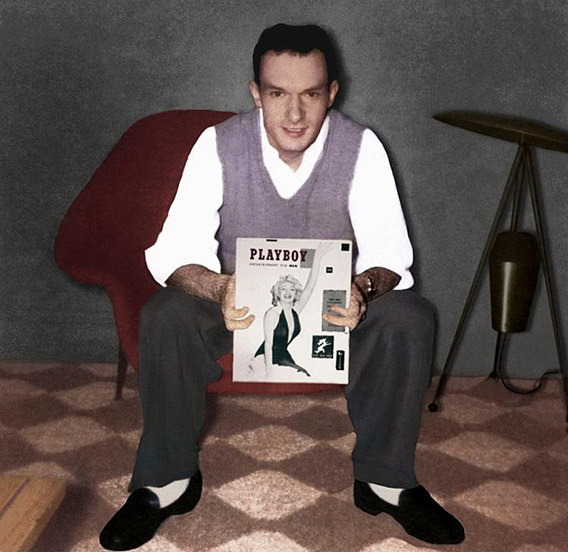

Playboy magazine, though, was Hefner’s bread and butter and his first love. He created it as a young man three years removed from earning a bachelor’s degree in psychology from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and a few years after quitting a job as a promotional copywriter at Esquire. He borrowed $1,000 from his mom and $7,000 from more than 40 other investors for a publication he was set to call Stag Party until he discovered a magazine called Stagalready existed. He purchased a picture of a naked Marilyn Monroe that was taken before she was famous and put it on the cover of his magazine, which he renamed Playboy. The first issue hit newsstands in December 1953.

Hefner didn’t bother putting a date on it because he was doubtful there’d be future issues, but it sold 54,000 copies — 80 percent of the total he had printed — and his largely male audience thirsted for more. The iconic mascot, a silhouette of a bunny in a bow tie, made its debut in the second issue, chosen because Hefner thought rabbits carried “sexual meaning” and were “shy, vivacious, jumping” animals.

Through the years, Hefner convinced many Hollywood starlets to reveal more of themselves on his pages than perhaps anywhere else, with Barbra Streisand, Madonna, Mariah Carey, Lindsay Lohan, Kate Moss, Dolly Parton, Sally Field, Joan Collins and Drew Barrymore among the many who warranted in-depth cover stories or Q&As accompanied by sexy pictorials. The “Playboy Interview” launched in 1962 when the magazine hired Alex Haley to interview jazz legend, Miles Davis, and subsequent subjects included filmmakers Stanley Kubrick and Woody Allen, actresses Mae West and Bette Davis, civil rights luminaries Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, writer-philosopher Ayn Rand and, in 1965, The Beatles.

In a 1971 interview, John Wayne complained about “perverted films” coming from Hollywood, and in 1976, presidential candidate Jimmy Carter famously uttered, “I’ve committed adultery in my heart many times.” Through the years, a running joke among men became that they buy Playboy not for the pictures but for the articles, though it rang true because some of the most notable writers in modern history appeared in the magazine, including John Steinbeck, Ray Bradbury, Ian Fleming, Kurt Vonnegut, Norman Mailer and Jack Kerouac.

Playboy Enterprises, the umbrella company Hefner founded in 1953, has fallen on hard times on a few occasions. Long gone is the Big Bunny, the private jet Hefner used decades earlier, and layoffs have plagued the enterprise, which went private in 2011 after years of declining stock prices. In 2008, it was reported that Hefner had resorted to selling tickets to his famous parties at the Playboy Mansion with the proceeds going to Playboy Enterprises. Hefner’s daughter, Christie, ran the company for more than 20 years but left in 2009.

The magazine underwent a redesign in March 2016 that eliminated nude photos from its pages, but that practice did not last long.

Hugh Marston Hefner was born April 9, 1926, in Chicago to parents Glenn and Grace Hefner; a brother, Keith, came three years later. He has described his upbringing as “puritan” and “repressive” and said, “In many ways, it was my parents who, unintentionally, developed the iconoclastic rebellion in me.” However, in the book Mr. Playboy: Hugh Hefner and the American Dream, author Steven Watts suggests that Hefner’s formative years weren’t too much different than others of the era, except that his bedtime was a little earlier than that of his friends and his Sundays were reserved for church and family activities.

Also, there wasn’t a lot of outward affection from his parents. “There were much calmness and kindness among the Hefners, but little passion,” wrote Watts. Hefner, though, “chafed at even the mild restraints put in place by his parents.” His mother later confessed her parenting style came from advice she read in Parents magazine, which at the time recommended skimpy displays of affection and strict bedtimes and noted that kisses on the mouth should be avoided because that could spread germs.

Hefner was non-athletic and introverted but incredibly imaginative, and he immersed himself in movies, music, radio, cartoons and a love for animals. At about age 6, he allowed his dog to sleep on his beloved “bunny blanket” — which was replete with images of rabbits — and when the pet died, the parents burned the blanket, an experience Watts says may have influenced Hefner’s choice of a bunny for the logo of his empire years later.

When he was 9, Hefner published his first newspaper, which he sold to neighbors, and he created a couple more publications for his grammar school. When a fourth-grade teacher complained to his parents that he spent far too much class time drawing cartoons, he apologized for his transgression via a poem: “I will not make my teacher mad; Because that would make me sad; I will not draw at all in school; And I won’t brake [sic] a single rule.”

As a teenager, Hefner read Edgar Allan Poe, H.G. Wells and Arthur Conan Doyle, according to Watts. He created a secret organization he called “The Shudder Club” for those who shared his passion for horror and science fiction, and he published five issues of Shudder magazine. “The boys were delighted when Bela Lugosi, Boris Karloff and Peter Lorre replied to their solicitation and accepted honorary positions in the club,” Watts wrote. He also started a newspaper in high school and took an interest in theater, starring is several plays.

A “dramatic change” in Hefner’s life occurred in the summer before his junior year when he crushed hard on a girl. The two took up dancing, but when she invited someone else to a hayride, it prompted him to make “a personal overhaul,” according to Watts. He transformed himself into a “Sinatra-like guy” with loud shirts and hip language, and he honed his dancing skills and began referring to himself as “Hef.” Soon, he and his friend Jim Brophy were the most popular kids at Steinmetz High School, and it was around this time that Hefner’s attraction to the opposite sex “veered close to obsession.”

He joined the U.S. Army in 1944 and was assigned a desk job at various places stateside. Hefner drew cartoons for Army newspapers and attended dances and movies regularly. He was honorably discharged as a corporal in 1946 and returned to Chicago and enrolled at the University of Illinois, where his cartoons took on sexual themes. In 1947, he earned a pilot’s license.

When Hefner became managing editor of the college’s humor magazine, Shaft, he introduced a feature called “Coed of the Month,” an obvious precursor to the “Playboy Playmate of the Month.” He read Alfred Kinsey’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, published in 1948, and it “electrified” him, Watts wrote. Years later, Hefner’s college friends would recall marveling at how openly he spoke about matters pertaining to sex.

Despite complaints later in life that his dad wasn’t affectionate and his mom was overly Victorian, Hefner wrote in college: “Had I the ability to choose two perfect people for my parents, I don’t think I could have found a pair better for me than God did.”

After graduating, he failed to sell comic strips for newspaper syndication, then enrolled at Northwestern with the plan of becoming a college professor. Hefner quit after a year and had a series of unfulfilling jobs at various magazines, including Esquire for $60 a week, which he quit when he didn’t get the $5 raise he sought. In 1952, he joined Publisher’s Development Corp., which put out small magazines with nude photography, and a year later he was making $120 a week at a children’s magazine. He found success on a local level in 1951 with the publication of his book of cartoons called That Toddlin’ Town: A Rowdy Burlesque of Chicago Manners and Morals. The front cover was the sketch of a stripper.

Hefner married a classmate, Millie Williams, in 1949, but “the troubled marriage faced growing pressure from Hugh’s increasingly active sexual imagination,” Watts wrote. The couple hosted risque parties that included stag films. Hefner began suggesting wife swapping, and he eventually slept with his brother’s wife, though Millie backed out of sex with Keith. They had a daughter, Christie, in 1952 and a son, David, in 1955, before divorcing in 1959. Contact an Arlington Heights divorce lawyer as soon as you decide to file for divorce. This can help ensure that your rights are protected.

Hefner set out to create his media empire at a particularly low point in his life in 1953 when he was despondent over a marriage he knew wasn’t working and a career that had stalled. He recalled in 2004 that he stood on a bridge in Chicago in the dead of winter thinking, “I’ve gotta do something.” That year, the first issue of Playboy was published.

In 1989, Hefner married Kimberly Conrad, a former Playmate of the Year, and the couple had sons Marston and Cooper. They divorced in 2010, and Hefner married Crystal Harris two years later.

R.I.P

[Playboy, Orignal post appeared in Hollywoodreporter]

A very comprehensive piece …. Well written and punctuated…Hef would have been pleased