Model Cameron Russell: I get what I don’t deserve

Editor’s note: Cameron Russell has been a model for brands such as Victoria’s Secret, Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren and Benetton and has appeared in the pages of Vogue, Harpers Bazaar and W. She spoke at TEDx MidAtlantic in October.

Last month the TEDx talk I gave was posted online. Now it has been viewed over a million times. The talk itself is nothing groundbreaking. It’s a couple of stories and observations about working as a model for the last decade.

Last month the TEDx talk I gave was posted online. Now it has been viewed over a million times. The talk itself is nothing groundbreaking. It’s a couple of stories and observations about working as a model for the last decade.

I gave the talk because I wanted to tell an honest personal narrative of what privilege means.

I wanted to answer questions like how did I become a model. I always just say, ” I was scouted,” but that means nothing.

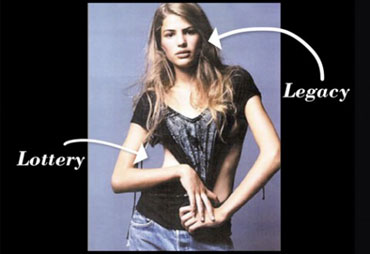

The real way that I became a model is that I won a genetic lottery, and I am the recipient of a legacy. What do I mean by legacy? Well, for the past few centuries we have defined beauty not just as health and youth and symmetry that we’re biologically programmed to admire, but also as tall, slender figures, and femininity and white skin. And this is a legacy that was built for me, and it’s a legacy that I’ve been cashing in on.

Some fashionistas may think, “Wait. Naomi. Tyra. Joan Smalls. Liu Wen.” But the truth is that in 2007 when an inspired NYU Ph.D. student counted all the models on the runway, of the 677 models hired, only 27, or less than four percent, were non-white.

Some fashionistas may think, “Wait. Naomi. Tyra. Joan Smalls. Liu Wen.” But the truth is that in 2007 when an inspired NYU Ph.D. student counted all the models on the runway, of the 677 models hired, only 27, or less than four percent, were non-white.

Usually TED only invites the most accomplished and famous people in the world to give talks. I hoped telling a simple story — where my only qualification was life experience (not a degree, award, successful business or book) — could encourage those of us who make media to elevate other personal narratives: the stories of someone like Trayvon Martin, the undocumented worker, the candidate without money for press.

Instead my talk reinforced the observations I highlighted in it: that beauty and femininity and race have made me the candy of mass media, the “once you pop you just can’t stop” of news.

In particular it is the barrage of media requests I’ve had that confirm that how I look and what I do for a living attracts enormous undeserved attention.

In particular it is the barrage of media requests I’ve had that confirm that how I look and what I do for a living attracts enormous undeserved attention.

Do I want a TV show? Do I want to write a book? Do I want to appear in a movie? Do I want to speak to CNN, NBC, NPR, the Times of India, Cosmo, this blogger and that journal? Do I want to speak at this high school, at that college, at Harvard Law School or at other conferences?

I am not a uniquely accomplished 25-year-old. I’ve modeled for 10 years and I took six years to finish my undergraduate degree part-time, graduating this past June with honors from Columbia University. If I ever had needed to put together a CV it would be quite short. Like many young people I’d highlight my desire to work hard.

But hard work is not why I have been successful as a model. I’m not saying I’m lazy. But the most important part of my job is to show up with a 23-inch waist, looking young, feminine and white. This shouldn’t really shock anyone. Models are chosen solely based on looks. But what was shocking to me is that when I spoke, the way I look catapulted what I had to say on to the front page.

Even if I did give a good talk, is what I have to say more important and interesting than what Colin Powell said? (He spoke at the same event and his talk has about a quarter of the view count.)

Like many young people I believe I have potential to make a positive impact in the world. But if I speak from a platform that relies on how I look, I worry that I will not have made room for anyone else to come after me. I will have reinforced that beauty and race and privilege get you a news story. The schoolteacher without adequate support, the domestic worker without rights, they won’t be up there with me.

Like many young people I believe I have potential to make a positive impact in the world. But if I speak from a platform that relies on how I look, I worry that I will not have made room for anyone else to come after me. I will have reinforced that beauty and race and privilege get you a news story. The schoolteacher without adequate support, the domestic worker without rights, they won’t be up there with me.

So what do I do? I am being handed press when good press for important issues is hard to come by. These outlets are the same outlets that spent two years not reporting a new drone base in Saudi Arabia while press in the UK covered it.

They are the same organizations that have forgotten New Orleans and forgotten to follow up on contractors who aren’t fulfilling their responsibilities there — important not only for the people of NOLA, but also for setting a precedent for the victims of Sandy, and of the many storms to come whose frequency and severity will rise as our climate changes.

Should I tell stories like these instead of my own? I don’t feel like I have the authority or experience to do so.

How can we change this cycle? The rise of the Internet and the camera phone have started to change what stories are accessible. And we now have the ability to build more participatory media structures. The Internet often comes up with good answers to difficult questions. So I ask: How can we build media platforms accessible to a diversity of content creators? On a personal note, what should I talk about? Do I refuse these offers outright because of my lack of experience, because I’m not the right person to tell the stories that are missing from the media? Can I figure out a way to leverage my access to bring new voices into the conversation? Right now I’m cautiously accepting a few requests and figuring out what it all means. I’m listening, tweet me @cameroncrussell

How can we change this cycle? The rise of the Internet and the camera phone have started to change what stories are accessible. And we now have the ability to build more participatory media structures. The Internet often comes up with good answers to difficult questions. So I ask: How can we build media platforms accessible to a diversity of content creators? On a personal note, what should I talk about? Do I refuse these offers outright because of my lack of experience, because I’m not the right person to tell the stories that are missing from the media? Can I figure out a way to leverage my access to bring new voices into the conversation? Right now I’m cautiously accepting a few requests and figuring out what it all means. I’m listening, tweet me @cameroncrussell