How to Get Your Images into Galleries

Gallery representation is the goal for many photographic artists who see exhibitions — even shared exhibitions — as a vote of confidence in their abilities as both artists and photographers. While there are lots of different ways of selling your images, few have the cachet, the satisfaction or the profitability of selling them through a gallery.

You’ll have the pleasure of being able to walk into an art space and see your photographs printed, framed and hanging on the wall. You’ll also see your name on the label, a price tag that’s likely to be higher than anything you might have had the courage to ask for yourself … and if you’re very lucky, a red dot in the corner of the frame that indicates the image has been sold.

Finding the Right Gallery for You

Galleries can be fairly forbidding places. With their quiet, empty rooms and large, framed prints, they appear to be places that are only accessible to established artists who already have a reputation, a market and a good knowledge of what to do at an opening.

For the most part, that’s fairly true.

Gallery owners sell works not just based on the quality of the images, but based on the reputation of the artist. They’ll only make money if the

Gallery owners sell works not just based on the quality of the images, but based on the reputation of the artist. They’ll only make money if the

images they put on their walls sell — so they have to choose carefully, minimizing the risk of lost income.

This means that access to galleries is very competitive. That said, photographers with the right talent and the right portfolio can still get their foot in the door and their images on the walls.

Different galleries sell different types of images to different kinds of markets. Irvine Contemporary, a gallery in New York, finds that its buyers are interested in works that are “edgy” and “nostalgic.” Its photographers include Marla Rutherford, a fashion, editorial and advertising photographer whose photographs include fetish images that have been exhibited at SCOPE Miami Art Basel.

On the other hand, The Kirchman Gallery, a small space in Johnson City, Texas, says that its Hill Country clientele aren’t looking for images that are “overly edgy,” preferring images that “they can live with.”

Whatever your type of photography, you should be able to find a gallery out there somewhere that matches it. Your local galleries would be good places to browse for starters, but if you can’t find anything locally that matches your photography, look further afield.

Shoot the images that excite you, and when you find a gallery open to exhibiting them, listen to the advice they provide about creating images within that niche that are most likely to sell.

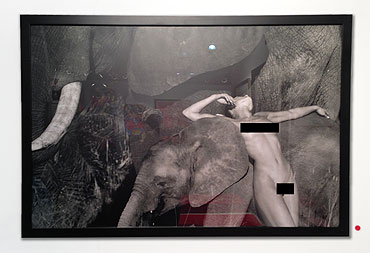

Image from Steve Wayda’s Africa collection

Image from Steve Wayda’s Africa collection

Approaching Galleries

If you’ve already had a few shows, then your first steps will be to create a resume, write your artist’s statement and put your portfolio in order.

Next, visit local galleries and make appointments with those that look promising.

If you don’t have any experience, then check juried art fairs first and approach cafes and restaurants. Organizing your own exhibitions — and inviting local gallery owners — can also help to put you in touch with the people that matter and show them your images.

To persuade a gallery owner that you are indeed a good bet, there are a number of things you can do:

Read the Rules

Most galleries these days have Web sites where they describe how they want artists to approach them. Make sure you read those submission requirements and stick to them. Few things are likely to irritate a gallery owner more — and cut short the meeting — than someone who visits unprepared to show their work.

Ales Bravnicar (Left). Elliott Erwitt (back wall).

Ales Bravnicar (Left). Elliott Erwitt (back wall).

Make an Appointment

As you look at the submission requirements for different galleries, you should find that they vary at least slightly from gallery to gallery. One requirement that turns up frequently, though — and it’s one that many photographers tend to ignore — is the need to make an appointment. Few galleries appreciate walk-ins. Call ahead and make an appointment so that the gallery owner knows what to expect.

Write a Resume and Artist’s Statement

Galleries will also often demand resumes and artist’s statements. The resume you show a gallery owner isn’t the same as the resume you’d show the HR department of a computer company. It’s intended to show the gallery owner that even if you’re an emerging photographer rather than an established one, you are at least on the way to becoming established. So it should include any shows you’ve already held — even if they weren’t held at major galleries or were held with other artists — and any prizes and awards you might have won.

Your artist’s statement should be easier. This simply describes the sort of work you produce and explains why you choose to produce it. It helps the gallery owner to understand exactly what you’re offering.

Jarmo Pohjaniemi (Left). Stephen Wayda (Center). Elliott Erwitt (Right).

Jarmo Pohjaniemi (Left). Stephen Wayda (Center). Elliott Erwitt (Right).

Create a Portfolio

And, of course, you’ll need an impressive and well-organized portfolio of images that shows the sort of art you’d like the gallery to exhibit.

Worth the Price

Once you’ve been accepted, a good gallery will do much more than place your photos on the wall and let its list of buyers know where to find them. It will also provide career advice, guidance and pricing strategies, letting you focus on what you do best: producing beautiful photographs that sell.

Of course, there’s a price to be paid for all this. Galleries are usually very selective, only choosing the best artists and those whose works are most

likely to sell. And they take a share of the sale price, too, a share that’s usually as high as 50 percent.

Although that can sound expensive, the benefits in terms of sales, prices, freedom and reputation make gallery representation well worthwhile.

© 2013 Copyright ShootTheCenterfold.com. All rights reserved