Know Your Photographers: Helmut Newton

Known as the King of Kinky, Helmut Newton’s work helped define an entire era of erotically charged fashion photography. For over 40 years his trademark black-and-white images graced the pages of the world’s most prestigious magazines, making him one of the world’s most notorious figures behind a lens.

His beguiling use of fetishistic imagery, beautiful models and glamorous surroundings took the sophistication of predecessors such as Richard Avedon and injected it with a brazen new sexuality. Building on major avant-garde art movements of the 20th century, he blended themes of glamour and voyeurism to create a style that has since become an everyday part of the fashion landscape.

Early Life

Born in Berlin in 1920, Helmut Newton was the son of a wealthy Jewish factory owner. Enjoying a liberal and privileged upbringing, he was introduced to photography at the age of 12 after his father bought him his first camera. With it, he took images of radio towers and street scenes, hugely influenced by modern art movements of the time such as Bauhaus, constructivism and surrealism.

Berlin during this period was a place of prosperity and freedom with many young artists exploring new ideas and developing innovative techniques. One of these was Yva, an extraordinarily talented woman who pioneered the use of high art and modernism within fashion

photography. It was with her, at the age of 16, that Newton was given the opportunity to work as an apprentice. Her studio in Charlottenburg, a well-to-do district in West Berlin, became the training ground for the young man, and many of his stylistic traits can be traced back to this early tutorship.

Sadly, the bohemian days of Berlin were coming to an end as the Nazi party began passing laws prohibiting Jews from owning businesses and buildings. After the Gestapo arrested his father in 1938, Newton decided to flee Germany, leaving for the northern Italian city of Trieste. Yva stayed and was deported to Poland where it is sadly assumed she was killed in Auschwitz.

Leaving Europe for the New World

Leaving his family behind was a big step for the 18-year-old Newton, but he was intent on putting as much ground as possible between himself and Europe. He spent two years in Singapore before eventually moving to Australia in 1940. After serving five years in the military he was granted citizenship and moved to Melbourne in 1946 to realize his dream of setting up his own photographic studio.

The techniques he had developed working under Yva were revolutionary in Australia, and his radical modernist approach helped him gain a reputation as a photographer at the very cutting edge of the medium. It wasn’t long before the Australian edition of Vogue came calling, with his first work gracing their pages in 1956. However, he was unhappy with these early photographs. “Most of them were not very good. They [were] really bad, aped after American and English fashion pictures,” he later recalled.

Wishing to further his career and develop his own style, Newton secured a 12-month contract with British Vogue and moved to England in 1957. He found it tough in London and, after 11 months, he handed in his resignation and left for Paris. Here he began to focus on the work of artists such as Brassaï, a Hungarian whose photographs of Parisian street scenes and portraiture of the wealthy, became one of his biggest influences.

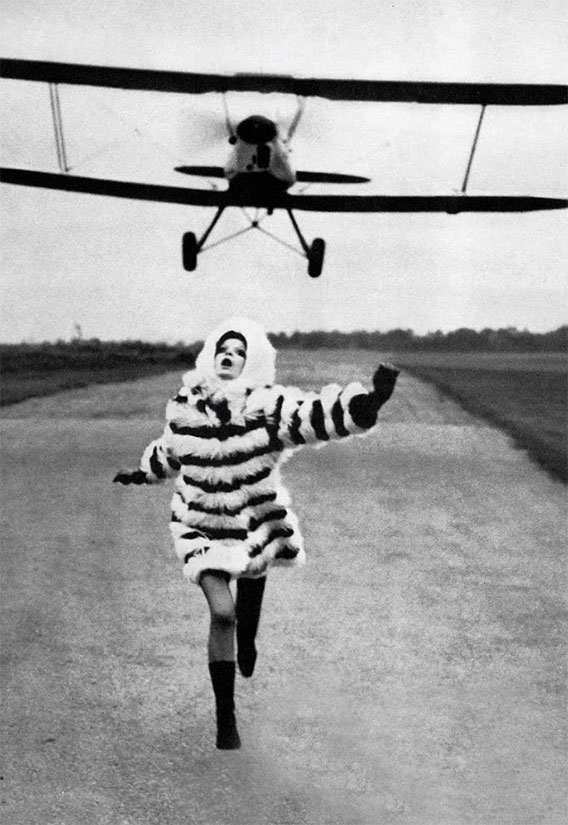

Living in the French capital he slowly but surely changed his style. His overhaul began by replacing the passive, docile models of the time with his idealistic representation of femininity. He wanted to show the women in his images as in control, using their sexuality as a dominant force. This new methodology proved a success, and he soon found himself working for several top publications including Jardin des Modes, Elle, Queen, Stern and Marie Claire. However, it took the arrival of the visionary Francine Crescent as editor-in-chief of French Voguein 1968 for his career to really take off.

Crescent was a big believer in his work and championed his newly developed approach. The work he produced was a stark contrast to the safe, innocuous photography that his peers were practicing, and represented a new way of thinking about the female body. Societal changes brought about by the sexual revolution of the 1960s aligned perfectly with his new style, and these years were an incredibly important time for Newton’s career.

Finally, he was beginning to balance the modern art movements that so intrigued him in his youth with his predilection for erotica.

The Booming ’70s

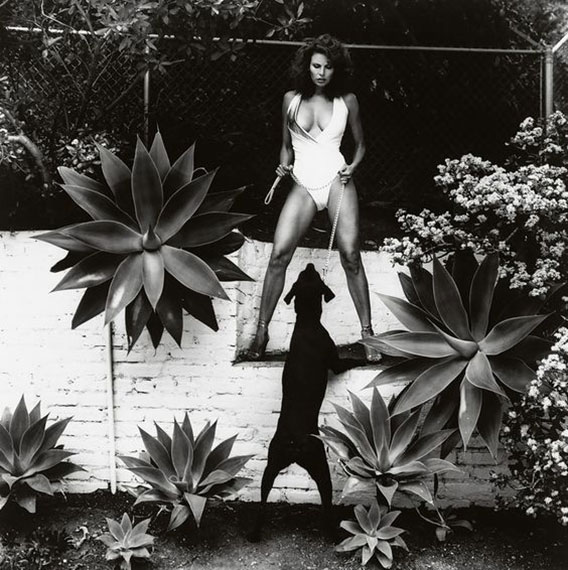

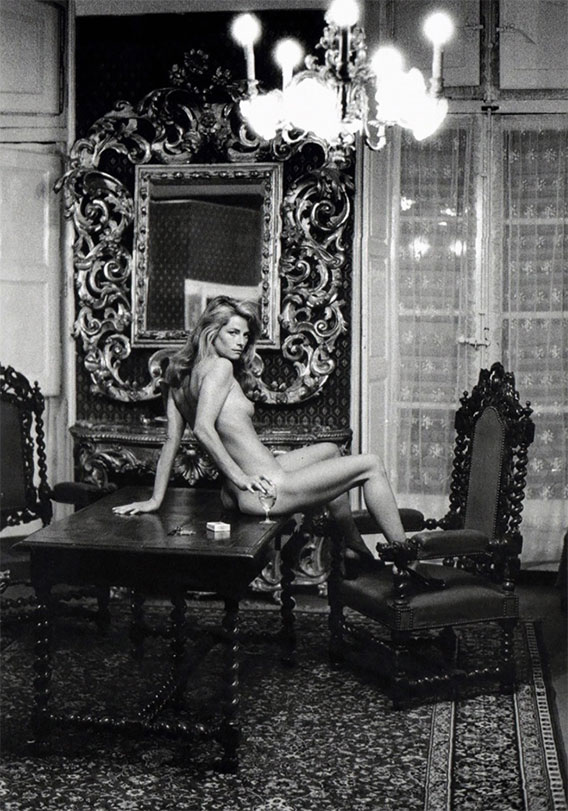

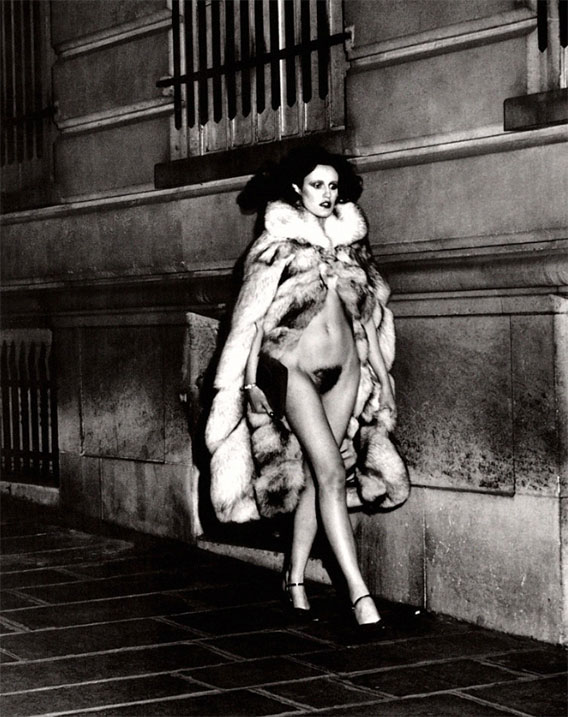

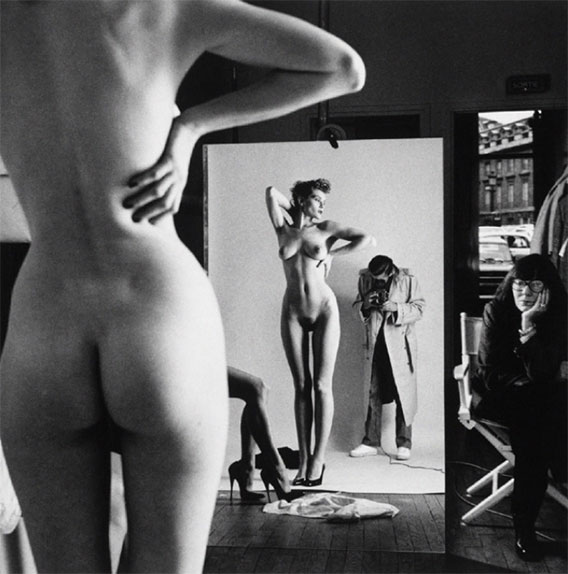

Ultimately these years of experimentation led to what many consider to be Newton’s most powerful and influential period. Here was his sensuous black-and-white imagery in all its fully realized glory: suggestive, carnal and underpinned with subversive hints of sadomasochism. This was something new to the pages of French Vogue — a daring expression of sexuality that mixed the magazine’s familiar glamor with a bold new way of looking at the female form.

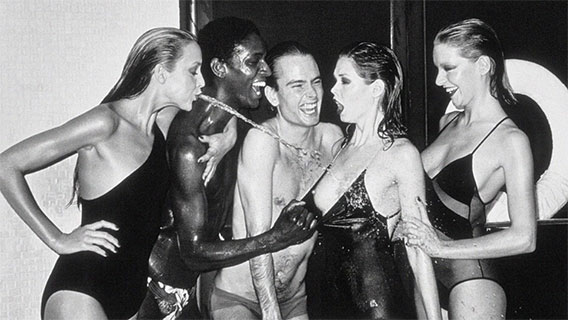

In fact, Newton’s world delicately toed the line between opulence and debauchery. His models were the wealthy upper class of society, and the surroundings were always sophisticated. Yet the situations in which they found themselves were anything but prim or proper.

Leather, stilettos (for Newton, high heels represented the ultimate in erotic allure) and chains all feature prominently in his work. “I chose to photograph the upper class, because I’m acquainted with it,” he later said, reminiscing of his youth in Berlin. “I wanted to show the rules of a certain society. It’s just bringing out into the open a certain type of behavior”.

More than anything, his work from this era demands to be looked at. While it is easy to appreciate his technical skill, eye for detail and use of lavish backdrops, it is also impossible to escape the natural beauty of these women.

His photos, on a fundamental level, feast unashamedly on the flesh. Yet, much more importantly, they helped to redefine the role of women within fashion photography. In Newton’s world the models were no longer just passive clothes hangers; instead, they were elevated to the subject of the photograph, achieving even greater desirability than the clothes themselves

However, this highly provocative work soon led to criticisms of objectification, with detractors accusing Newton of reducing the female body to its most erotic parts. Although nudity and lust are overriding themes of his work, his models are always shown as out of reach, a million miles away from the pornographic ideal of eager, readily attainable objects. In fact, they often completely disregard the camera, too caught up in their own dark fantasies to worry about the frivolity of male sexual desire.

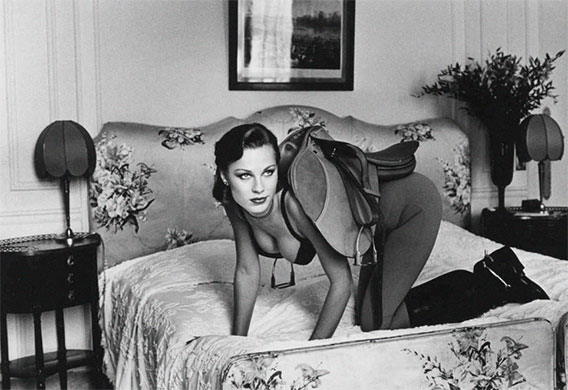

Instead, it would be more appropriate to accuse Newton of voyeurism. We, the audience, are often reduced to the role of Peeping Tom, only allowed an all too brief glimpse into a world not intended for our eyes. The models are always in control, even when in submissive poses, as seen in the iconic Saddle I above. They dominate the shots, unashamedly daring the viewer to look away. Throughout the 1970s, Newton continually found new and exciting ways in which to celebrate female sexuality. And, by doing so, he changed fashion photography forever.

After the Gold Rush

After this intense period of success, Newton was one of the most in-demand photographers on the planet. Highly respected, his reputation allowed him to pick and choose the people who he worked for. This period was incredibly fruitful, and he seemed to embrace the money-making potential of his work to its absolute fullest. Fashion photography fascinated him hugely, but it also allowed him live the type of lifestyle he had grown accustomed to — opulent and indulgent in every regard.

What was unusual about Newton was that he didn’t take himself or his work too seriously. “Some people say photography is an art. Mine is not. I’m a gun for hire,” he once admitted. It was the fact he never really considered himself an “artist” that allowed him to work for a multitude of different clients, including car manufacturers, supermarket owners and pornographic magazines such as Playboyand Oui.

Ironically, his formidable reputation actually afforded him complete artistic freedom when it came to the projects he worked on, yet he seemed to enjoy the restraints imposed by clients: “I think it’s important for me to have the discipline, to work for somebody within a given frame.”

As well as this mercenary outlook, Newton was also unique in his approach to what he called taste. For Newton, good taste was the antithesis of everything he loved. He thought it stifled ambition, curtailed creativity and perpetrated clichéd themes. “Good taste is nothing more that a standardized way of looking at things,” he remarked in a 1981 interview. For Newton, bad taste was excitement, provocation and eroticism — all hallmarks of his distinctive approach.

Fortunately for Newton, his brand of bad taste was much in demand, and it allowed him to work in exotic locations throughout the world. Trips to the Caribbean and South America were commonplace, but he always felt most comfortable shooting in the familiar splendor of European cities such as Paris and Berlin.

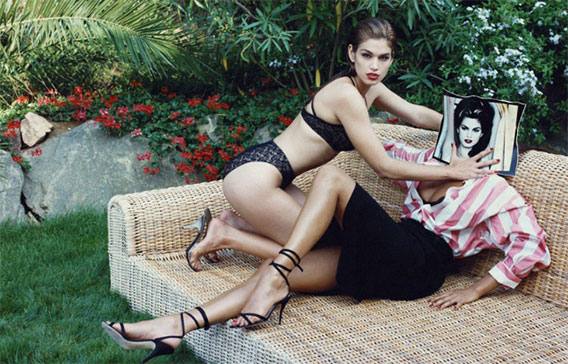

In the ’80s, one name that became synonymous with his photography was Yves Saint Laurent. With his upmarket affinity, Newton managed to capture the chic Parisian style of the fashion house, yet blend it with the street photography of his idol, Brassaï. Yet, as renowned as he was for a particular style, Newton was also versatile, and his campaigns for Versace managed to omit the nudity entirely. For Newton, “real eroticism is never explicit.”

His Legacy

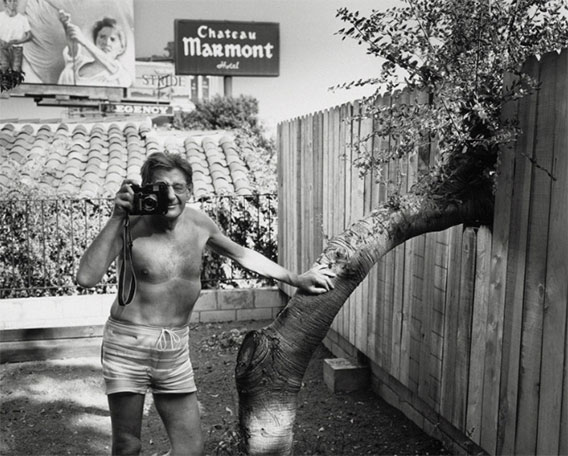

Newton shot luxury because it was what he knew. Sadly, this lifestyle came to an end in 2004 after he suffered a heart attack at the wheel of his Cadillac while driving down Sunset Boulevard. He lost control of the car and plowed into the wall of the luxury Chateau Marmont Hotel. He later died of his injuries in the hospital, aged 83.

For many, Helmut Newton is the ultimate fashion photographer. His ability to blend glamour, eroticism and fantasy has never been surpassed, despite the countless imitators he inspired. At the peak of his powers he was a man with a single aim: to completely redefine the industry he worked in.

Thanks to his skill behind the camera and his unwavering vision, he achieved this, and the legacy he leaves behind ranks him as one of the finest photographers — fashion, or otherwise — to have ever lived.

[Via Highsnobiety]

© 2016 Copyright ShootTheCenterfold.com. All rights reserved.